I had an interesting conversation with a friend a few years ago

For the past several years Kei has been importing riding horses to Japan from Germany and early on I helped her out with correspondence, drawing up preliminary contracts, and so on. The reason she came to me is that, as I have mentioned elsewhere, I once lived in Germany and can still understand the language somewhat. Kei only knew a handful of words: ja, nein, danke schön, bitte. In the kingdom of the blind, they say, the one-eyed man is king.

Fortunately for her and me, most of the Germans we were dealing with spoke damn good English. (That wasn’t the case in the 1980s.)

Two years later, her business has expanded with small, yet encouraging steps and has had her traveling to Europe on a monthly basis, shopping for horses, investing in them, and participating in international equestrian events as a judge. Reading this, you might get the impression that Kei is a fabulously wealthy woman, but nothing could be further from the truth: she is, in fact, a modestly working class, single mother who has gotten by on her wits and creativity. I have a lot of respect for the woman.

Anyways, Kei will be making two trips to Germany again next month to introduce a German breeder/trainer to her Japanese client who’s interested in buying a “high level horse”. Until now, Kei has been buying horses with somewhat humble pedigrees for eventing [1] enthusiasts and riding clubs in Kyūshū and was excited to finally deal in some top level horses.

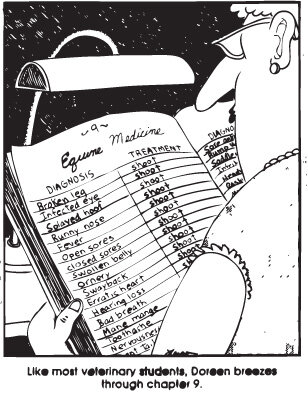

Hearing this, I joked that there were four levels of horses: high-level, mid-level horses, low-level, and glue.

This is where the conversation became interesting.

Kei laughed then told me about a local company called Kohi Chikusan owned by a Mr. Kohi (sounds like the Japanese pronunciation of coffee). Kohi, she said, takes “compromised” horses off of stables’ hands and “makes arrangements for them”. Some of these horses are put down, some are resold and show up, seemingly miraculously, at rival stables, and a few are sold for horsemeat. (Don’t worry, most of the horsemeat used in the delicacy basashi[2] comes from Australia.)

“Whenever a horse acts up or doesn’t respond well,” Kei said laughing, “we tell it we’re going to call Kohi-san.”

I couldn’t help but be reminded of the scene in George Orwell’s classic Animal Farm when Boxer is sent to the glue factory.

I tried to google Kohi Chikusan, but couldn’t find anything.

“They don’t have a website,” Kei said.

“No, I don’t suppose they would.” Talk about a niche business!

Kei explained that they had to use the service because when a horse weighing five hundred kilos dies it’s nearly impossible to move it. Rigor mortis sets in within a few hours after death, freezing the horse in the position that it died in, and the only way to get it out of a stable is to chain it to the back of a tractor and drag it out. Not exactly the kind of thing you want your paying customers to see when they’re practicing their jumps.

“So, whenever a horse becomes too ill for the veterinarian to treat, we call Kohi-san.”

“Kohi isn’t a very common name, is it?” I said.

“That’s because he’s a Buraku-min,” she replied matter-of-factly. “A lot of people involved in that kind of business come from the Buraku-min. Meat handlers, too.”

This morning when I was looking into the family names of the Buraku, I learned that while the caste system of feudal Japan was abolished in Japan in the early years of the Meiji Period and all Japanese were assigned family names, the Buraku-min were given family names that would make them still recognizable from ordinary Japanese a hundred years later. These names apparently include the following Chinese characters: 星 (star); body parts, such as 手 (hand), 足 (foot), 耳 (ear), 頭 (head), 目 (eye); the four points of the compass, 東 (east), 西 (west), 南 (south), 北 (north); 大, 小 (large and small); 松竹梅 (pine, bamboo, plum), 神, 仏 (god and buddha) and so on. Examples include: 星野 (Hoshino), 小松 (Komatsu), 大仏 (Osaragi), 神川 (Kamikawa), 猪口 (Inoguchi/Inokuchi)、熊川 (Kumakawa)、神尾 (Kamio), and so on. (Beware of assuming that everyone with these kinds of names are Buraku-min, they are not.)

I wrote about the Buraku-min in Too Close to the Sun. The passage from my novel discussing these unlucky people has been included below:

In the afternoon, I’m summoned to the interrogation room where Nakata and Ozawa are waiting for me.

Both of them are in an easy, light-hearted mood today. The desk is free of notebook computers; there are no heavy bags filled with thick folders of evidence on the floor.

Ozawa is slouched comfortably in his seat, tanned fingers locked behind his head.

"What was the name of that Korean restaurant you mentioned last week?" he asks.

"Kanō," I say, taking my usual seat, still bolted to the floor.

"Where was that again?"

"It's in Taihaku Machi, a rough neighborhood near the Chidori Bridge."

"Taihaku Machi?"

"Along the Mikasa River, across from Chiyo Machi."

"Chiyo? Ugh!" he says grimacing. "Why is it that all the good Korean restaurants have to be located in the shittiest part of town?"

Nakata asks me if I know what Eta is. I shrug.

Ozawa tries to look it up in his electronic dictionary, but can't find it.

"Figures," he grumbles.

"How do you write it," I ask.

Ozawa scribbles the following two kanji in his notebook: 穢多 The first character, 穢, he says, can be read as kitanai and means filthy. It can also be read as kegare. Finding the entry, Ozawa spins his dictionary around to show me that kegare means impurity, stain, sin, and disgrace. The other, more common character, 多, pronounced ta, or ôi, means plenty, or many. So, eta, connotes something that is abundantly filthy or impure.

Then it hits me that the eta Nakata is alluding to is yet another word that editors of Japanese-English dictionaries conveniently omit: buraku-min (部落民).

Map indicates “Eta Mura” or the area where the outcasts lived.

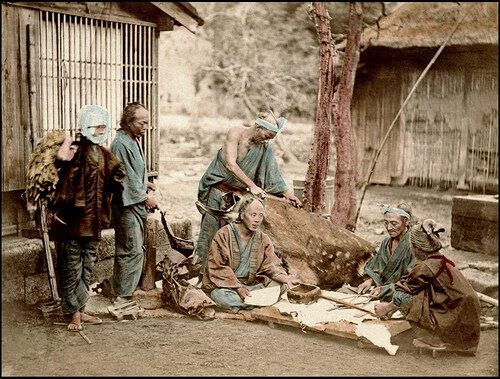

The Buraku-min (lit. hamlet people) were a class of outcasts in feudal Japan who lived in secluded hamlets outside of populated areas where they engaged in occupations considered to be vitiated with death and impurity such as butchering, leather working, grave-digging, tanning and executions.

For the Shintō who believed that cleanliness was truly next to godliness, those who habitually killed animals or committed otherwise heinous acts were considered to be contaminated by the spiritual filth of their acts and thereby evil themselves. As this impurity was believed to be hereditary, Buraku-min were restricted from living outside their designated hamlets (buraku) and not allowed to marry non-Burakumin. In some cases they were even forced to wear special costumes, footwear, and identifying marks.

The Emancipation Edict of 1871 intended to eradicate the institutionalized discrimination and the former outcasts were formally recognized as citizens. However, thanks to family registries, known as koseki, which are assiduously kept by officials in every Japanese city, town and village, it was easy to identify who was Buraku-min from their ancestral home, and discrimination against them continued.

Shortly after coming to Japan, the wife of a company president once confided to me that she and her husband might be willing let his daughter, God forbid, marry an ethnic Korean, but would never countenance her marrying a Buraku-min. He would never hire one, either.

"Never? Regardless of the person's talent?" I asked.

"The damage to the image of my husband's company would be far greater than any benefit such an employee could ever bring."

And that's how it goes in this sophisticated democracy: you can still be discriminated against just because your great-great-great grandfather had a shitty job.

Today there are some four thousand five hundred Dôwa Chiku, or former Buraku communities that were designated by the government in the late sixties for the so-called assimilation projects. Over the next three decades, housing projects and cultural facilities were constructed, and infrastructure improved in the dowa chiku (assimilation zones) to raise the standard of living of the residents of those areas.

There are an estimated two million descendents of Buraku-min in Japan today, most of whom live in the western part of the country, particularly in the Kansai area around Osaka, and in Fukuoka Prefecture.

"Chiyo’s a Dōwa Chiku," Nakata says. "Crawling with Eta."

"I know," I say.

“You do?” They seem surprised.

The fact was first brought to my attention many years ago when I was searching for an apartment. A kindly old woman I had just met was all too eager to help me. She pulled out a map of the city from her handbag and, without elaborating, began crossing out "undesirable places", many of them located along the rivers. When I asked why, she said: "Trust me, you don’t want to live there." And so I did, finding a reasonably priced one-room apartment in one of the tonier areas near Ōhori Park.

"Those people are nothing but trouble," Nakata says. "Riffraff the lot of them."

"You’re kidding, right?"

He leans forward, resting his rotund chest against the desk. "There were a lot of Eta in my hometown when I was young. Nothing, but trouble. If you ever got in a fight with one these Eta bastards, the next thing you know, you're surrounded by a group of them. Sneaky guttersnipes."

The thought of Nakata as a chubby little kid in glasses getting the snot beaten out of him by a gang of Buraku boys almost causes a laugh to percolate out of me.

"Surely not all of them?" I say.

"Yes, all of them," Nakata replies and sits back, brushing his wimpy salt and pepper mustache with his fingers.

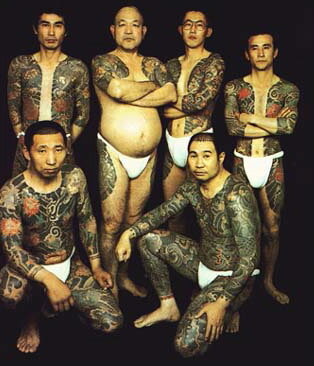

Ozawa asks if I've heard of the Yamaguchi Gumi.

"The yakuza gang?"

"Yeah. Biggest crime syndicate in Japan. It's mostly comprised of these Eta scum."

"Most yakuza gangs are," says Nakata.

"I had no idea," I say.

"Nothing but trouble," Nakata says again.

"Say, what's the deal with the girls working the food stalls at the festivals," I ask. "I've heard they're run by the yakuza."

"They are. The girls are Eta bitches," Nakata replies.

"Pretty damn cute bitches," I say.

Dregs of Japanese society or not, quite a few of the young girls working at festivals are knockouts.

After fifteen years, Japan can still be an enigmatic country. One thing I've never been quite able to figure out is why the best-born Japanese girls are so homely. The ugly daughters of good families, I call them.

"Cute they are," says Ozawa snickering. "Cute they are. Every evening in Chiyo you'll see small armies of the chicks all dolled up hopping into taxis. Off to Nakasū. Shoot the breeze with one of them and some yakuza prick will strut on up and start breakin' your balls as if you were hitting on his woman. That's when the badge comes in handy, of course. Hee-hee."

"I wouldn't go near one of those girls with a barge-pole," Nakata pipes in.

As if the man has to beat the girls away with a stick.

"There's something I've been meaning to ask you," I say.

"Shoot," says 0zawa.

"A lot of the guys in the joint here, and last week at the jail at the Prefectural Police Headquarters, for that matter, are obviously yakuza."

"Yeah?"

"I don't get it."

"Don't get what?"

"In the States, there is, among so many crime syndicates, the Cosa Nostra, the Sicilian Mafia, right? You know, The Godfather, and all that. Well, these guys used to bend over backwards to deny that the Mafia even existed. Here in Japan, though, the yakuza practically advertise their criminal activity with missing pinkies, lapel pins, and bodies covered in tattoos."

It borders on the absurd. If cops were seriously interested in taking a bite out of crime, the first thing they ought to do is clamp down on these shady characters. The police, of course, will counter that they aren't in the business of preventing crime: they can't make any arrests until a crime had been committed. Which begs the question of why someone like me has to molder away in a stinking cell.

"The ones who strut and swagger," Ozawa says, "are good-for-nothing punks. All bluster and no brawl. They kick up a fuss because they don't have the balls to actually do anything. No, the yakuza you really have to watch out for are the quiet ones, the ones who never raise their voices, or show their tattoos. Those bastards will whack a person at the drop of a hat."

“Better get a hat with a strap then.”

Thank you for reading. This and other works are, or will be, available in e-book form and paperback at Amazon. Support a starv . . . well, not quite starving, but definitely peckish: buy one of my books. (They’re cheap!) Read it, review it if you like it (hold your tongue if you don’t), and spread the word. I really appreciate it!

© Aonghas Crowe, 2010. All rights reserved. No unauthorized duplication of any kind.

注意:この作品はフィクションです。登場人物、団体等、実在のモノとは一切関係ありません。

All characters appearing in this work are (wink, wink) fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.