If you have been watching this year's Taiga Drama "Segodon", you may find yourself having to contend with one of Japan's more baffling dialects, Kagomma-ben, or the Satsugu/Kagoshima dialect which is spoken within the former Satsuma and Ōsumi provinces of souther Kyūshū.

Rather than attempt to explain it--although I have married into a Kagoshima family and am still confused after eleven years--I will provide a key to some of the more commonly used phrases in the drama.

「~たもんせ」

~ tamonseis the same as ~ kudasai (please)

Kagomma:「こいしか着るものがなかで、こんとおり許してやってもんせ」

Koi shika kiru mono ga naka de, kon tōri oriyurushite yattemonse.

Standard:「これしか着るものが無いので、このとおり許してください。」

Kore shika kirumono nai node, kono tōri yurushite kudasai.

Translation: This is all I have to wear, so please permit me to . . . like this.

Kagomma:「お助けくいやったもんせ。」

O-tasuke kui yattamonse

Standard:「お助け下さいませ。」

O-tasuke kudasaimase

Translation: Please help me!

「おはん」

"Ohan" means anata or omae (you)

Kagomma:「おはんらに地球儀を見せたかったが」

Ohanra-ni chikyūgi-o misetakattaga.

Standard:「お前らに地球儀を見せたかったが」

Omaera-ni chikyūgi-o misetakattaga

Translation: I wanted to show you guys a terrestrial globe, but . . .

「おまんさあ」

"Omansā" is a more formal way to say anata-sama (Thou).

「~さあ」

"Sā" when added to a name means "sama" (〜様 )

Kagomma:「西郷さあ」

Saigō-sā

Standard:「西郷様」

Saigō-sama

Kagomma:「兄さあ」

Nii-sā

Standard:「兄様」

Nii-sama

Translation: (Elder) Brother

「じゃっどん」

"Jaddon" is the same as "demo" or "shikashi" (but); note that if you leave the final ん (n) off, it has the opposite meaning, そうだ (sō da). Although, this word is a familiar to many Japanese (thanks in large part to dramas like "Segodon"), it is seldom used today in Kagoshima.

Kagomma:「黒か色を買いたかっじゃっどん」

Kuroka-iro-o kaitakajjaddon.

Standard:「黒い色を買いたかったんだけど」

Kuroi iro-o kaitakattan dakedo . . .

Translation: I wanted to buy a black one, but . . .

Note: Japanese often leave things unsaid and sentences unfinished.

Also note that "black" is not kuroi (黒い), but rather kuroka (黒か). Replacing the i (い) with ka (か) to adjectives is fairly common throughout Kyūshū. You will often hear the word yoka (良か, good, okay, alright) in the drama. Yoka is also commonly used in Fukuoka today.

「~すっど」

"〜suddo has the same meaning as "suru-zo" (するぞ ), an emphatic way of stating that you will do something. A common way to cheer someone on in the Kagoshima dialect is to shout (チェスト) "Chesuto!" which can be confusing for English speakers. It was for me at first. チェスト is a contraction and corruption of 強くすっど (Tsuyoku suddo!) to つぇすっど (Tsue suddo!) and then チェスト!I might translate this as "Give it all you've got!"

「そいやっとに」

"Soi-yatto-ni" means "sore-nano-ni" (〜それなのに ); where soi is the Kagoshima, and possibly Kyūshū pronunciation of sore ("that"); and yatto-ni is the Kagoshima equivalent of nano-ni ("and yet", "but").

Kagomma:「そいやっとに日本を離れちょっとはどげんこっじゃろうか」

Soi-yatto-ni Nihon-wo hanarechotto-wa dogen kojjarōka

Standard:「それなのに日本を離れているとはどういうことだろうか」

Sore nano-ni Nihon-wo hanareteiruto-wa dōiu koto darōka

Translation: And yet, if [you/I] leave Japan, what will happen/what will that mean? (Note: it's not clear about whom Saigo is speaking here from this quote from the novel Segodon.

「せつなか」

"Setsunaka" is how "setsunai" (切ない) is pronounced in Kagoshima, with the adjective ending 〜い (〜i) being replaced with 〜か (〜ka) just as it is in many parts of Fukuoka, Saga, and I believe Nagasaki. I suspect that the same is true in Kumamoto, but I need to double check. Northern Miyazaki and Ōita may be exception. Will look into this later.

Setsunai (切ない) is one of those words that doesn't quite translate. My trusty dictionary offers "painful" and "heartbroken". "Painfully sad" might be a better translation. Or even "heart-wrenching". The ol' Kokugo Jiten says it is the feeling of your chest being tightly screwed or constricted, or feeling miserable and wretched, helpless even.

Another translation of setsunaka is yarusenai (遣る瀬無い) which again means miserable, wretched, helpless and frustrated. No bowl of cherries.

Kagomma:「せつなか話ですよね。」

Setsunnaka hanashi desuyone.

Standard:「切ない話ですよね。」

Setsunai hanashi desuyone.

Translation: It's a heart-breaking story, isn't it.

Note: In Saga there is also a similar sounding, but unrelated word, setsunaka, that means "cramped, tight" (窮屈) or "narrow" (狭い).

「帰ってくっと」

"Kaette kutto" simply means "kaette kuru" (return, come back).

Kagomma:「一緒に帰ってくっとがあたい前の話じゃろう。」

Issho-ni kaette kutto ga ataimae no hanashi darō.

Standard:「一緒に帰ってくるのがあたり前の話だろう。」

Issho-ni kaette kuru-no ga atarimae no hanashi darō.

Translation: It's a matter of course that we will come back together. (→ Of course, we'll come back together.)

Note: The "r" in "ri" (り) is often dropped in the Kagonma dialect. ありがとう (arigatō) is pronounced あいがとー (aiigatō), and in the above example あたり前 (atarimae) is pronounced あたい前 (ataimae).

「くっと」

Similar to the example above, "kutto" means "kuru" (come, arrive, get to, show up).

Kagomma:「そげな日がくっとでしょうか。」

Sogega hi-ga kutto deshōka.

Standard:「そんな日が来るとでしょうか。」

Sonna hi-ga kuru to deshōka.

Translation: Such a day will surely come.

Note: Sogena (そげな) as you might surmise means "such a, like that, that kind".

「そんせい」

Sonsei is simply how "sono sei" (for that reason, because of that) is pronounced.

Kagomma:「そんせいであめりかでは木綿をつくることが出来もはん。」

Sonsei-de Amerika-dewa momen-o tsukuru-koto dekimohan.

Standard:「そのせいであめりかでは木綿をつくることが出来ません。」

Sonosei-de Amerika-dewa momen-o tsukuru-koto dekimasen.

Translation: For that reason, they can't make cotton in America.

Note: Not sure what reason they are talking about here. It might be a reference to the American Civil War which coincided with the end of the Edō Period. Dekimohan is obviously dekimasen (cannot be done). ま (ma), I find, is often pronounced も (mo).

「あたい前」

Ataimai is another example of the "r/l" being dropped from "ri" (り). Atarimae (当たり前) is pronounced ataimae (あたい前), just as arigatō (ありがとう) is aigato (あいがと).

Kagomma:「一緒に帰ってくっとがあたい前の話じゃろう。」

Issho-ni kaettekutto ga ataimae no hanashi jarō.

Standard:「一緒に帰ってくるのがあたり前の話だろう。」

Issho-ni kaettekuru-no ga atarimae no hanashi darō.

Translation: Of course we'll be returning together.

Note: Atarimae/Ataimae is a pretty useful word that can mean "Of course", "It's only natural that . . .", "No wonder", "You bet", "Absolutely", and so on. Darō added at the end of a sentence indicates a supposition or guesswork. The speaker may not be 100% certain, but thinks so. Interestingly, while it is pronounced jarō in Kagoshima, the word most commonly used in the north of Kyūshū is yarō.

Many, many years ago when I was visiting Tōkyō for the first time, my girlfriend hid her face in embarrassment when I used yarō. What's so funny, I asked.

"You sound like a hick from the south."

I hadn't realized at the time that I was speaking Hakata-ben.

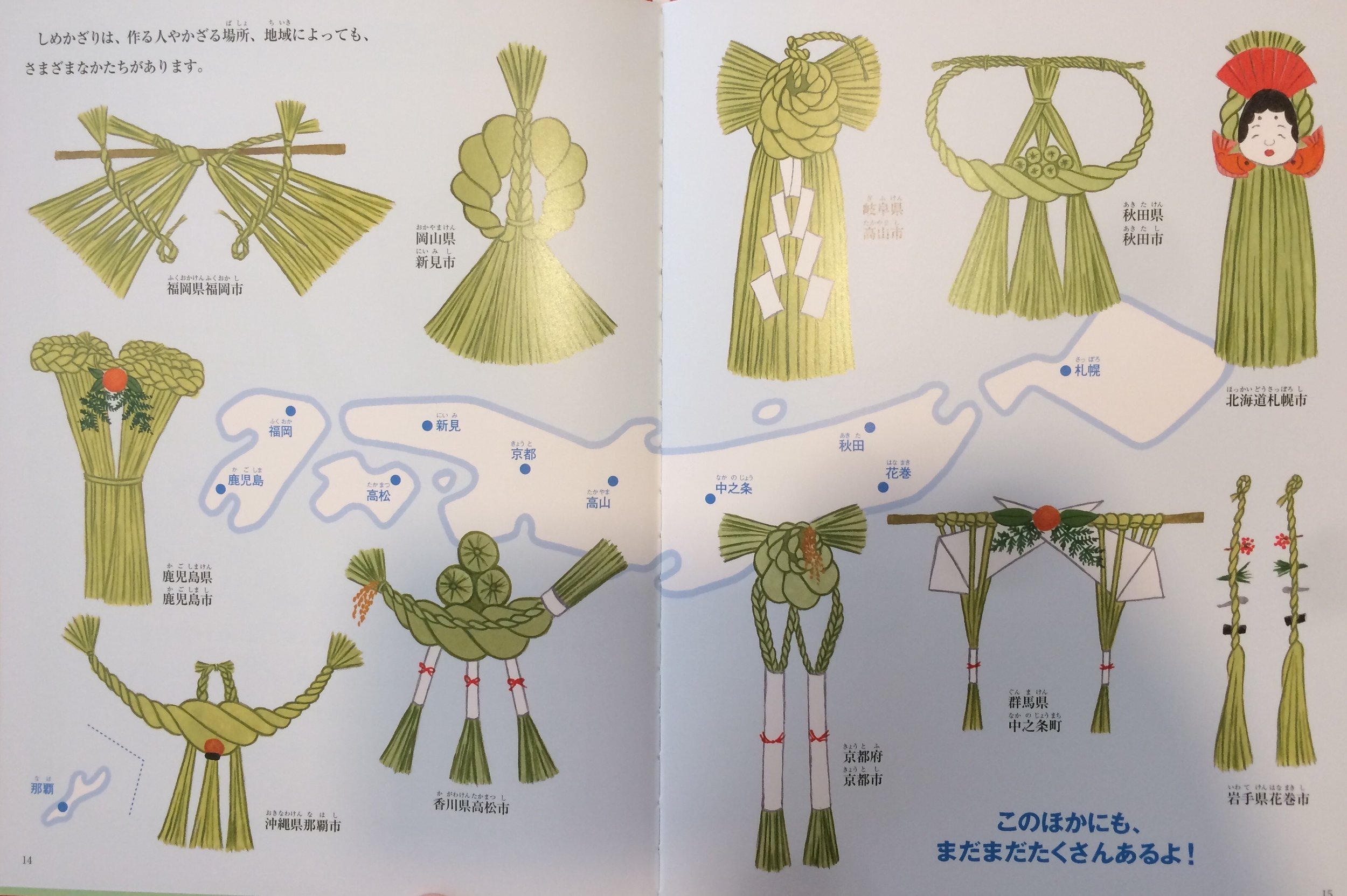

Looking at the map below, however, you can see that in northern tip of Kyūshū, jarō and yarō are both used, while the rest of Kyūshū save for the the purple bit around Kumamoto people say jarō (red).

For more on the Kagoshima Dialect, go here.