The boys' undōkai (運動会, field day) has been postponed by two weeks and is now called a gakunen-betsu taiiku happyōkai (学年別体育発表会) or Presentation of Physical Education Separated by Grades. (Trust me, it sounds marginally better in Japanese.) What would normally be an all day affair under a blazing hot sun will now last about 30 minutes per grade. Win-win.

I'm the Sole Survivor

The kids are now in their second week of school after Golden Week, which is always a tough time for any student here. Gogatsu-byō, they call it. (Lit. May Disease, but can be translated as post-vacation blues.)

One of the kids in my elder son's class has stopped coming to school altogether, much to my son's delight. (The two go to the same dojo and have hated each other since kindergarten.) The kid hadn't been doing his homework (of which there is a pile every day) and was doing poorly on the tests. (This is all hearsay, so I can't really verify.)

Seems kids like to push buttons at the start of the year to see how much they can get away with and my sons, because of the way they look (i.e. not Japanese) tend to get picked on first, which is one of the reasons I had them take karate from such an early age. One kid made fun of my elder son's name, so he went up to him, stared him down, and in his deep voice--a la Robert De Niro--said something like, "You talking to me?" And that was the end of that. He can break baseball bats with one kick and the other kids know it, so he is able to manage these little pests fairly easily.

My younger son is more the lover than the fighter type, slightly more sensitive than his big brother, but still scrappy. He said that one of the kids called him "Amelika-jin". Now, I'm not the rah-rah U! S! A! meathead type, but this kind of thing just pisses me off, especially when you consider history, geopolitics and so on.

When my son told me about it later, I told him that the next time some idiot says something like that, say: "Hey, twinkie, would rather be speaking Russian or Chinese?"

Fact of the matter: if it weren't for America--warts and all--Japan would be a very different country today.

My wife was listening and said, "You're Daddy's right. You boys are lucky to be American. Those passports alone, Do you know how much those are worth???"

I turned to my wife and said, "From now on, I would like you to greet me in the morning with 'Thank you, America!'"

And we laughed it off.

From experience, these little trials don't last very long. Again, it seems kids like to see how much they can get away with before the teacher steps in and puts a stop to it. We've been lucky with our teachers in that regard.

Yesterday, during our morning walk, I noted that our elder son's school load sure was ratcheted up since entering the fifth grade. He has I think 10 subjects now and all of them really demand a lot of the student. Math, which, is taught sometimes 6-8 times a week in the earlier grades to really make things sink in, is only taught 4 times now, but the content is much more difficult. The typical American high school student would probably be stumped. And that's just math. Then there's Japanese and even more Chinese characters to remember how to not only read, but write. Science and Social Studies are also vigorously taught, if you can say that. At any rate, they really take each and every subject dead serious.

We're fortunate, though. The boys, while they wouldn't mind having less homework every day, seem to be enjoying their studies and keeping up well enough.

I told my wife that education in Japan reminded me of a game I used to play as a kid called Stay Alive where the "sole survivor" is the one who manages to not lose his marbles and get into Tokyo University.

According to the missus, of the 400 students at Shuyukan, Fukuoka’s most competitive public high school, only one or two are able to get into Tokyo University, the country’s most prestigious uni. Only one to three graduates get into Kyōto University, Hitotsubashi, Ōsaka. Half of them, however, are able to enter Kyūshū University. Among the 400 students at Jōnan High, the second tier public high school, only one can pass Ōsaka or Kyōto University. 50 get into Kyūshū U.

It’s amazing how competitive places at those top universities are.

Junior High Enrollment Rates

In 2019, the percent of Japanese students attending private junior high schools nationally was 7.4%. In Tokyo, however, a quarter of all students do. It is not uncommon for parents there to decide upon a place to live only after an oldest child has passed his/her private junior high school entrance exam.

Since 2015, there has been a slight, but steady increase of 0.1 percentage points each year. I suspect that with the household budgets being squeezed due to COVID-19, the percentage attending private junior high schools will drop somewhat.

I was talking to a third year junior high school student yesterday about private junior high schools in Japan. She said that of her elementary school, only 20 out of the 200 six graders went to private junior high schools.

One went on to Nada in Hyōgo, considered the best in the nation; 5 went to Kurume Fusetsu, the highest ranked in Fukuoka Prefecture; 3 went on to Ōhori; 2 to Waseda Fusetsu in Karatsu, Saga; 2 to Seiun (don’t know this school); 3 to Jōchi, a Jesuit school associated with Sophia University in Tōkyō; and 2 went to Chikujo, a Buddhist girls school. She couldn't remember where the other two went.

To get into a private junior high school usually requires students to spend a lot of time cramming at juku (private evening schools) in the later years of elementary school. The girl I was talking to only attended in the sixth grade, which she admitted was too late. She had classes four days a week from 5 in the afternoon to 9 at night. She usually went to bed around 11 because of all the additional homework she had to do.

During the school breaks, she attended week-long overnight study camps, which she admitted were rather unpleasant experiences. The juku she attended cost about ¥60,000 a month. Her junior high school now costs ¥50,000 a month, plus other fees. So, to get into a "good" private junior high school, you'll have to fork over up to a million yen a year ($9,000), then continue paying a similar amount for the next six years for private school tuition, or $60-80,000 all together even before university.

While that seems a bit stiff, it’s still a third of the eye-watering tuition my Jesuit high school now charges. I really don’t know how people are able to afford it on top of their home mortgages payments and health insurance premiums, and car loans, and, and, and . . . And I'm not poor. Just fucking stingy.

Head of the Class

This was originally posted in the spring of 2013.

With my wife in the hospital suffering from exhaustion (she's fine now) and Grandma out of town, I was left with two options: take the day off or bring my three-year-old son to work. (If a Member of Congress can do it . . .)

Anyways, I sent the above photo to my family and all everyone wanted to know was why the girls were wearing surgical masks. (Now that we are in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, only red necks would ask a question like that.)

Could be a number of things, I wrote back:

1. They may have a cold and don't want it to spread. (Thoughtful.)

2. They don't want to catch another person's cooties. (Paranoid.)

3. They have hay fever and are trying to keep it from worsening. (Probably too late.)

4. They are trying to avoid breathing in the smog that China exports to us along with other low-cost, high-externality crap. (Understandable, but most likely meaningless.)

5. They have herpes. (Gotcha. Keep the mask on.)

6. Or, they have merely overslept and didn't have time to put their faces on. The girls are too embarrassed to show their face. (Now, you'd think it would be more embarrassing to wear a silly mask like that in public, but what do you know, you silly gaijin?)

A few days later, I asked the two girls in the photo why they had been wearing masks that day and learned that it was, as I expected, because they hadn't been wearing make-up. "What's the big deal," I said. "I'm not wearing make-up myself!"

This is a fairly new phenomenon: young women in Japan didn't use to do it, say, five years ago. You may read into that what you like.

Kindy Bus

I took my son, Yu-kun. to kindergarten this morning (by means of Mama-chari) and managed to arrive at the very same time as one of the school busses.

The kids all clamored out of the bus and were herded by two teacher to the main gate of the school where they put their hands together, bowed deeply, and shouted in unison: "Hotoke-sama, ohayō-gozaimasu! Enchō-sensei, ohayō-gozaimasu!" (Good morning, Buddha! Good morning, Mr. Principal!)

It was my first time to see this, and I must say it was quite adorable.

Yu-kun also takes the school bus from time to time depending on the weather and my wife's energy level. (He rode it yesterday but ended up vomiting all over himself and had to be sent back home.)

The “pink bus”[1] usually doesn’t come rolling into our neighborhood until a few minutes after nine in the morning (which is why we often just drop him off ourselves around eight).

When the bus comes to a full stop, one of the teachers hops out, grabs the kids and tosses them in like sacks of recyclables. Once on board, the kids are free to sit wherever they like. Yu-kun sometimes sits in the very front next to the driver, sometimes in the middle near a girl he has a crush on, and sometimes in the very back like yesterday (which may be the reason why he threw up).

The kids are usually dressed in a variety of uniforms. Some wear the whole get-up with the silly Good Ship Lollypop hats and all, while others wear their colored class caps. Some are in their play clothes, a few in smocks, and fewer still wear their school blazers. Anything goes really and that’s fine by us.

A year and a half ago, my wife and I were considering four different kindergartens. Two were Christian, one Buddhist, and a fourth was run by what appeared to be remnants of the Japanese Imperial Army’s South Pacific Division.

It was this fourth kindergarten that initially appealed to us. The kids were said to be drilled daily and given lots of chances to exercise and play sports outside, something that offered us the possibility that our son would come home every afternoon dead tired.

Well, in the end, that school didn’t want us. (So, to the hell with them!) We went for the free-for-all Buddhist kindy, instead.

I think we made the right, albeit expensive, choice.

The other morning, I happened to see the bus for the Fascist kindergarten. Although it pulls up at the very same place where Yu-kun usually catches his own bus, the similarity stopped there. For one, all the kids were wearing the same outfit with the same hats, the same thermoses hanging from their left side. When they got in the bus, they did so in an orderly fashion, the first child going all the way to the back, the second child following after and sitting in the next seat. The bus was filled from the back to the front and I wouldn’t be surprised if the children filed out of the bus in the same orderly manner. Once seated, the kids sat quietly. It was at the same time both impressive and horrifying.

[1] I still have no idea why it is called the “pink bus” because nothing on it is pink. Every time Yu-kun says, “Oh, the pink bus!” I scan it from bumper to bumper to try and figure out how on earth he can tell it’s the pink bus and not the “yellow bus” which is actually yellow.

The Buddhist kindergarten is popular with parents who are doctors. I once asked a mother why and she replied that she wanted her children to just play and play and play before they had to knuckle down and start cramming from elementary school for their entrance exams. Poor kids.

Hoops of FIre

Oh, the joy of being an American citizen!

I am finally getting around registering my second son as a Yank, three years after his birth. (Sorry, son.) For those American expats, who are soon to become parents this can be an exasperating, time-consuming process, which entails, in addition to a stiff drink for the patience you’ll find in it, completing the following forms:

DS-2029, Consular Report of Birth Application.

DS-11, Passport application.

SS-5, Social Security application.

The original birth certificate which requires a visit to the Ministry of Justice if the child is a “half”, something I learned only after getting into an altercation with a senior employee at the local Ward Office. (This is so unlike me, but those SOBs at the Ward Office have a way of bringing out the worst in a person.) This, of course, needs to be translated into the blessed Mother Tongue: ‘Murrican.

An affidavit of the child’s name. (Now, one thing nice about the U.S., is that they allow you to choose a name different than the one on the Japanese birth certificate if you like. Your daughter can, for example, be named Hanako Yamada in Japan and Bianca X. Witherspoon in the U.S.)

The original, plus one photocopy, of the parents’ marriage certificate, which in my case will require going back to the ward office, and apologizing for the misunderstanding the other day. (Sigh.) Oh, yes, this needs to be translated into English, too.

Original plus one photocopy of proof of termination of all prior marriages. (As if going through with the divorce wasn’t painful enough, now I have to beg the Ward Office to provide proof that I am a scoundrel. They’re on to me.)

Evidence of parents’ citizenship, original plus one photocopy.

Evidence of physical presence, such as high school and/or college transcripts (which I actually do have and like to whip out from time to time to prove what a marvelous student I was. No one believes me. The impudence!), wage statements (Wages? Y’gotta be kidding. Why do you think I came to Japan in the first place, silly?), credit card bills, former passports, etc.

Both parents’ IDs. Originals and copies, but of course.

The application fee. Now we’re getting somewhere.

Mug shots of the child for the passport.

One self-addressed, “LetterPack Plus” envelope.

Two days in and I’m just scratching the surface of paperwork. Fortunately, the Tokyo Embassy’s website (see Citizen’s services) does an outstanding job in walking you through the process. They also provide templates for translating the necessary Japanese documents.

Now, back to the paperwork. Better fortify myself with another gin and tonic before I take that next step.

Student Loans, Japanese style

Look up the word shōgaku-kin (奨学金) in any Japanese-English dictionary and you will, more often than not, be told that the word means "scholarship". It does not. Unlike scholarships in the U.S. which are awarded on the basis of academic achievement and do not have to be paid back, shōgaku-kin is a student loan.

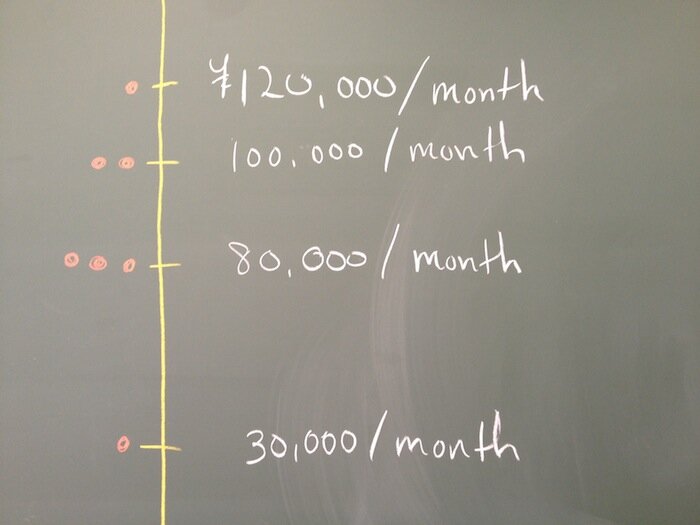

Of the thirteen girls in my class this afternoon, seven of them were recipients of these shōgaku-kin loans which ranged from ¥30,000 per month to as much as ¥120,000 per month ($285~1,142). The most common amount was ¥80,000 per month ($762), with three of the seven receiving that amount.

As tuition runs about ¥450,000 ($4,286) per semester at the private college were I work, a loan of ¥80,000 per month is more than enough to cover the expense of education. (Now, compare that to my own university where it costs more than $60,000 a year to study.)

The loans must be paid back, of course. Students are given a grace period of six months before they must return the money, at which time they will start making monthly payments of ¥142,000 to ¥20,000 ($152~190). They have ten years to pay off the loan. Interest on the principal of the loan is negligible: less than one percent. (Again, compare that with the U.S. where I was paying a fixed 10% interest.)

All in all, it's not a bad deal.

For those of you like me who would like to avoid saddling their kids with debt so early in their lives, there is the gakushi hoken (学資保険) or yōrō hoken (養老保険) which is a kind of savings and life insurance plan. Many of these plans start at as little as ¥10,000 a month and usually have a fixed payment period of about five years. It’s a quick, painless, and safe way to sock away money for your kids’ education.

This is Sparta

This weekend the local boy scout troop is doing their annual overnight Bataan Death March: elementary boys (and girls as the scouts here are open to both sexes) will be marching 30km; junior high schoolers, 60 km; and high schoolers, 100km.

Out of curiosity I checked what kind of mileage a Marine recruit puts in over his 13-week-long bootcamp and came up with about 200 miles (320km), which is nothing compared to what these Japanese kids are doing in one night.

Welcome to Sparta!

Note: Looked into the “Bataan Death March” and learned that, one, it was about 100 km long, give or take 5 kilos, two, half of it wasn't on foot, but in rail cars, and, three, it took place over a period of about three days. It always sounded like hell on earth to me—and I'm sure it wasn't easy (heat, lack of potable water)—but, geez, little Japanese boys and girls here are doing it overnight with little more than a water bottle and a couple of o-nigiri. These kids are tough!

Jeepers, Creepers

This is a story “Wacky”, the owner of a number of shoe stores here in Fukuoka, related to me the other day:

"A high school boy came into my George Cox shop this afternoon and asked if I remembered him. I replied that I didn’t, but when he told me that he had come to the shop with his father six months earlier it all came back to me.

"He had come with his father to try and get his old man to buy a pair of Creepers for him. During the hour or so that the two of them were there, we talked about all kinds of things and I mentioned a high school girl who had once come to the shop. She, too, had wanted to get someone—her grandmother, in this case—to buy the shoes for her. I told her that shoes like these—at ¥37,000 they aren’t cheap, after all—weren’t the kind of thing you should be trying to get someone purchase for you.

"When the boy heard that, it gave him pause and he decided against having his father buy them. Instead, he went out and got a job at a convenience store, and for the next six months he worked part-time before and after school, saving what he earned. And now he was back at my shop, wanting to buy the shoes with his own money."

I joked that Wacky should have refused to sell the kid the shoes and chewed him out instead for breaking school rules by getting a job. “The little brat should have his nose in a textbook right now and not thinking about shoes and fashion and other nonsense.”

Kidding aside, though, I had to admit that it was quite a lesson the boy had learned and told Wacky so: “He’ll treat those shoes with the utmost care now that he knows what it took to buy them. You may have very well just saved the boy from a life of indolence and purposelessness.”

Prison Break

Many children in Japan—the active ones, in particular—are amateur entomologists. Whenever they go out, they invariably return with bags and boxes and hands full of bugs. Today my family and I went to Mount Kizan (基山) in Saga Prefecture. No sooner had we got there than my wife and younger son started foraging through the tall grasses for insects. The hunt produced several grasshoppers and one huge preying mantis.

When we were leaving, the mantis caught one of the grasshoppers and bit its head off. It then proceeded to chomp the rest of its prey, save the wings and skinny forelegs. It is at the same time both disgusting and fascinating to watch a mantis in action, close up. Trust me on this. (Think Gladiator, only with exoskeletons and wings.) On our way home, my wife and sons fell asleep in the back seat. I was seated in the front seat, window open, elbow sticking out when I felt something crawling on my head. Then I heard what sounded like the fluttering of wings. At first, I suspected that a bug had flown into the car. It wasn’t until about fifteen minutes later when my wife woke up that I understood what had happened. “The mantis has escaped!!!” While my wife was asleep, her grip on the bag had weakened and the bug managed to crawl out. It then climbed up the back of my seat and onto the top of my head and flew out the window.

Unfortunately for the mantis it didn’t get very far. It rode for the next ten minutes on the top of our car, holding on for dear life.

Gotta Naraigoto

Ask a group of Japanese under the age of, say, thirty-five if they'd had lessons—what the Japanese call narai goto or o-keiko—when they were young, and you'll probably find most, if not all, did. Having been in the Eikaiwa (English conversation) trade for many years and having personally taught many preschool and elementary school aged children, I know from experience that Japanese children maintain schedules that would have American kids on their knees, crying, "Uncle!"

The whole business of training, cultivating, and educating children would be interesting to research some day. In the meantime, here are the results of a half-arsed survey I did the other day.

Of the twenty university sophomores (18♀/2♂) that I surveyed, 17 had had lessons of some kind before starting elementary school. By the time they had enrolled in elementary school, all of them were taking some kind of lesson. The most popular lessons were piano (15), swimming (13), calligraphy (11), and English and cram school, i.e. juku (10). Asked if they would also send their own children to these kinds of lessons, 19 said yes. The type and number of lessons they would like their children to take, however, changed.

I've long been interested in knowing not only what people studied and when, but also whether they feel they had benefitted from the lessons and whether they would do the same for their own children. Most, it appears, feel they did and would make their future children do likewise.

As a father myself the time will come soon enough when I will be forced to decide if I will make my own son take these kinds of lessons and what I will have him study. I am already leaning towards lessons in a third language, guitar, calligraphy, soccer, abacus, and swimming. The poor kid.

I originally wrote this blog post back in 2011 when my elder son was only a year old. Now that he is almost nine, I can say that the third language probably won’t happen until high school—getting the boys to be bilingual is hard work enough—musical lessons won’t happen unless they decide to pick something up themselves. Calligraphy? What was I thinking? That said, the older boy has nice handwriting thanks to his mother’s constant berating. The final three narai goto have worked out alright. The boys love soccer and have played on “teams” for several years now. Abacus, or soroban, can’t be more highly recommended. As for swimming, with their tight schedules it’s hard to put them in regular lessons, so we drop them off at intensive courses every long holiday. In addition to those, the boys have been doing karate two to four times a week. They also have English lessons with Daddy a few times a week.

Unlimited

無限の可能性

Unlimited Possibilities

As I watch my boys grow, one of the things I often hear them say is “Daddy, I can now do this or that!” It doesn’t matter if it’s their studies or sports, they are constantly developing, maturing, getting better, learning, playing, mastering new things.

As I age, I find the opposite is true. There are things I can no longer do or, worse, things I think I am no longer capable of doing. Negativity is part of aging and to fight it I need to be more positive. Not in a silly Pollyannic way, but in a way that is rooted in reality. The possibilities may not be unlimited, but they are still there if you have an open mind and are willing to push yourself to try new things. Visiting this shrine in Kyōto reminded me of that.

Fifty, shmifty. I can do it.

Carpool Dad

At my son’s Tuesday evening soccer practice again.

It may sound silly to admit this, but I had no idea child-raising would be as time and labor intensive as it has been. For example, just getting the kids ready for school and kindergarten eats up a good two hours of my weekday mornings. (This should improve once they are going to the same school and are once again on the same schedule.) Then, there’s taking them to all their extracurricular activities and lessons and often having to hang around until they are finished—because in Japan you don’t just drop off and pick up; no, you’re expected to observe and then drill the kid later at home.

The evenings are occupied with making sure homework gets done and understood, providing the boys with opportunities to hear, read and speak English. Then there’s the feeding and cleaning up after them, getting them bathed and ready for bed, and finally reading book after book after book before succumbing to exhaustion and having to do it all over again.

Not that I’m complaining. I love watching my boys grow up, learn or master new things, overcome challenges. I wouldn’t give it up for the world. That said, I wouldn’t mind being able to sleep in every once in a while.

Fufu Bessei

Ask a simple question—i.e. “If you are a foreigner currently or formerly married to a Japanese citizen, did your spouse keep his/her Japanese family name after getting married to you?”)—and you will surely get an angry reply like this:

"I was married to a Japanese man, and yes - he kept his name. You seem to be assuming that the only people who marry foriengers are Japanese WOMEN. I happen to be a foreign woman who married a Japanese man. I kept my name because it's my name - why would I change it? Women don't "belong" to their husband; why should they change their name?"

Ugh. I wasn't assume anything. And why do you assume that as a man I was assuming something? Sheesh.

Statistically, Japanese men are far more likely to marry foreign women than Japanese women. This is something I have known for years. They tend, however, to marry other Asian women (Chinese, Filipino, Korean, Thai, etc.). Japanese women, on the other hand, marry in decreasing order Koreans, Americans, Chinese, British nationals, and so on.

What I am trying to look into—again, no assumptions; that’s why I’m asking—is what motivates people (particularly Japanese women) to either keep their Japanese maiden name or take their husband's upon marriage to a foreigner. Also, what motivates foreign men/women to adopt their Japanese spouse’s family name?

Ultimately, what I want to look at is what family name Western parents of half-Japanese children (i.e. children who are likely to look "half") are choosing for their kids and what motivates it. I also want to know what challenges, if any, they may have had if they had chosen the Western family name.

One of my friends is half Japanese/half American, but looks for the most part like a Japanese man. Since his wife is Japanese, their children look, as you would suspect, Japanese. But, they all have his American family name written in katakana on their name tags at school. Whenever they change schools/grades and are introduced to new classmates, everyone is surprised by how good their Japanese is. Seeing the American name, the other kids brains assume the kids are 100% American rather than 75% Japanese.

As for my own children, they look very . . . hard to say. They don't look Japanese at all, but they speak Hakata-ben and have my wife's family name. Wherever we go, people look at the boys and start speaking in broken English to them.

Here are some stats on "international marriage": http://www.lifeaaa.jp/27.html

If you are a foreign resident in Japan who is married to a Japanese national, please have a look at this short survey at Survey Monkey.

Blasphemy

My wife made an interesting observation after spending the day with an old friend: "Ideas about the proper way to raise children are like a religion. It's like I belong to this sect. My friend belongs to another sect. And just like you shouldn't say 'My God is the One True God and yours is a blasphemy.' it's hard to tell someone that their way of raising a child may be wrong."

She was referring in particular to the Boob Tube and how some families have the TV on all day long like BGM in their homes. "How can you talk to your children or read to them if you've always got the TV on?"

As with religion—you won't really know if you were right or completely wrong until you die (even then you still may not have an answer)—when it comes to kids, you won't know if your policies worked until the kids grow up and go out into the world.

The other day, our sons (“Cain and Abel”) were at their grandparents. (Heaven on earth!) I plopped down on the sofa and looked at the black screen of my TV. I thought about turning it on to watch the news, but the effort to get off my arse and do so was too much. Inertia has a way of keeping you verring out of habit. It occurred to me that for many people the effort required to turn off the TV and open a book, instead, is often too much for many people, too.

The magazine Keiko to Manabu, a subsidiary of Recruit, publishes an annual survey on extracurricular activities.

After School Activities in Japan

I have been trying to put a piece together on extracurricular activities in Japan with comparison to the situation in the States. There are loads of stats on naraigoto (習い事, after school lessons) here, but much less information concerning extracurricular lessons and activities in America. The Census Bureau claimed that 6 out of 10 kids in the US participated in some kind of extracurricular activity, but didn’t give much detail as to what kind or how often. One interesting nugget in the report was that only 8% of children in America were taking part in all three activities (i.e. sports, clubs, and lessons) at the same time. Children referred to those in grades K-12.

As for our family, my second-grade son does karate 2-4 times a week, soccer 2-3 times, soroban (abacus) once a week, and English once a week with his friends from kindergarten. He has mini English lessons with me a few times a week in addition to the lesson with his friends. During school breaks, we enroll him in swim lessons. For half of last year, he was in a shōgi (Japanese chess) class a few times a month. His 6-year-old brother has a similar schedule, minus the shōgi, and soccer is only once a week. In the winter months, I take the boys ice skating every other week.

Living downtown as we do, almost all of the lessons are a short walk away.

When my elder son was in his infancy, I had ideas about what lessons I would have him take—English, of course, but also calligraphy, classic guitar, and so on. None of that happened, except for the English.

His first activity was Play School. A bit expensive, but highly recommended. Shortly after he entered elementary school, though, he grew tired of it. Karate became the focus. At first it was only 1-2 times a week, but after getting his arse whooped in a tournament, he told his mother that he wanted to become stronger, so she started taking him to the main dōjō. Soccer was started as a way to maintain the friendships with his kindergarten friends but last year he changed teams, again in order to be a better player. Soccer is his passion at the moment and he doesn’t mind going to every practice. He insists even though he is exhausted afterwards.

The other day, I was walking past the Eishinkan Juku (cram school) just as the kids were getting out. It was Saturday evening and they kids looked as if the life had been sucked right out of them.

Cram schools like Eishinkan offer tests free to the public as a way to, one, check the level of the eggheads who study at their school with that of non-juku kids, and, two, to scare parents whose kids don’t go into following the herd and sending their own children as well. It’s a funny business.

We had our boy take the test a few weeks ago are now waiting the results. Ideally we would like to avoid jukus as long as possible, but I wonder how feasible it is. At the moment only a handful of his second grade classmates go, but by fifth grade apparently it’s the reverse. Even kids who are not going to take a private junior high school’s entrance exam go to juku which always has me scratching my head.

The Keiko to Manabu report had some interesting stats on narai goto in Japan.

44% of kids surveyed engaged in one extracurricular activity. 34% two part in two. 16% had three. 5%, like our sons, had four.

40.8% of kids had swim lessons

27.7% had English lessons

20.3% Piano

14.1% Calligraphy

13.5% Cram School

12.8% Gymnastics

8.6% Soccer

7.1% Soroban/Abacus

5.1% Other Sports

4.3% Dance

4.3% Karate

Toka Ebisu Festival

One of the nice things about living in Japan is that there is always some festival or holiday to look forward to. Unlike America where once the holiday season ends with New Year's or, ho-hum, the feast of the Epiphany on January sixth, there is a long lull in festive events, in Japan something fun is always just around the corner. Once Christmas has passed, the trees come down and up go the kadomatsu and other New Year's decorations. After the five or six-day drinking, eating, and TV-viewing binge known as O-Shôgatsu, or the Japanese New Year, comes Tôka Ebisu, a festival honoring Ebisu, the patron deity of businesses and fisheries. At around the same time, the Coming-of-Age Day celebration celebrating the entry into adulthood of the nation's twenty-year olds, is held. There is the bean-throwing exorcism known as Setsu-bun in early February, as well as a number of local festivals held in shrines and temples in the meantime.

On Sunday, I went to Fukuoka's main Ebisu shrine which is located just outside of Higashi Park. While I sometimes miss the New Year's celebrations do to travel, I always manage to get back in time to attend the Tôka Ebisu festival.

Like most other festivals held throughout the year in Japan, you'll find the usual demisé food stalls selling o-konomiyaki (below), jumbo yakitori, and so on. What makes Tôka Ebisu different, however, is the number of stalls selling good luck items featuring the seven lucky gods (Shichi Fukujin) of which Ebisu is one, talismansand other trinkets to ward off bad luck, and so on.

The festival also attracts a much different class of people. Whereas you can see many young men and women at the harvest festival Hôjoya (also known as Hôjoe), the people attending Tôka Ebisu tend to be older and "tarnished", making it an interesting place to people watch. I never fail to find the middled aged mamas of "snacks", rough-looking men who look as if Ebisu hasn't been very generous to them, and others desperate for an auspicious start to the new business year.

This year, there seemed to be far more people at the festival than usual. Perhaps it was the weather, perhaps it was that after the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami everyone is hoping for a bit of luck.

Sweet roasted chestnuts.

If you look closely at the apex of the crowd in the picture above you can see an upside down red fish, a sea bream. This is a symbol of Ebisu who is often depicted carrying one. In Japanese the sea bream is called tai which rhymes with medetai, meaning “happy”, “auspicious”, or “successful”. Real sea bream are often displayed at a celebratory gatherings, such as New Years, the end of sumô tournaments, engagement ceremonies, and so on.

Just beyond the red sea bream is a procession of the Hakata Geiki, a troupe of geisha working in Fukuoka City. I’ll write about them in a later post in the coming months. Incidentally, the photo on the cover of my second novel, A Woman’s Nails, was taken at this event several years ago.

The geisha making their way to the shrine. This procession is held every year at the height of the Tôka Ebisu festival and worth seeing. This year we just happened to be there when it was taking place.

Another feature of Tôka Ebisu is the drawing that is held at the shrine. On either side of the shinden there are booths selling tickets.

The first time I attended the festival was over ten years ago and didn’t know what to expect. So, when I pulled out one of the lots from a hexegonal box and the Shintô priest shouted, “Ôatari!” (Jackpot!), my mind filled with delicious possibilities: a new car? A trip to Hawaii? Cash? I had never ever won so much as a cakewalk or bingo game before. Needless to say, I was quite excited.

As another priest pounded out several beats on a drum and shouted “Ôatari,” the first priest pulled out a huge red fan from a pile of trinkets and talismans behind him and passed it to me. The fan had 商売繁盛 (shôbai hanjô, “prosperity in business”) written on it in large white characters. Prosperous was the last thing I felt.

That didn’t stop me, however, from going back year after year and trying my luck. In the past, the tickets were only ¥1,500. Today, they go for ¥2,000 each—so much for the deflationary pressure we are told has been pushing prices lower and lower—and where I once bought two or three of the tickets, I now only buy one.

Over the years I have “won” two of those large red shôbai hanjô fans, a massive wooden paddle as big as a cricket bat that has 一斗二升五合[1] written on it, a plate featuring Ebisu-sama, a wooden piggy bank, a calendar, and a small Ebisu doll.

A dutiful follower of this cult of Ebisu, I went on the tenth of January last year. The weather was awful—freezing cold and rainy—and I had been forced to wait under a canopy that leaked like a sieve for a good hour and a half until my wife and son showed up.

When they finally did, I was in a foul mood. My pant legs and shoes soaking wet, the cold was beginning to seep into my bones.

“Let’s just get the damn thing and head on home, okay?” I grumbled to my wife. “It’s freezing!”

We hurried into the shrine, which thanks to the lousy weather was not as crowded as it usually can be during the festival. There was only a handful of people in line for the drawing.

Well, no sooner had we handed over our ¥2000 at the reception desk than the man at the counter said, “Congratulations, you’re our twenty-five-thousandth visitor.” Or something like that. He had us fill out a form and then asked us to follow him to the place where the lots were drawn. After handing the form to the priest with the box containing the lots, I was told to pull one of the sticks out. It didn’t matter which. I did so and gave it to the priest who stood up and, turning on a microphone, said he had a big announcement to make.

“We have a major prize for our twenty-five-thousandth visitor today!” Another priest started banging away at a drum. The other priests in the shinden stopped what they were doing, stood up, and started clapping in unison. After a number of Banzais, the priest handed over a massive and cumbersome bamboo rake to me. It was adorned with ceramic depictions of the gods Ebisu and Daikoku, a red sea bream, a bale of rice, and other auspicious items.

Let me tell you, I couldn’t have been more thrilled had I won a trip to Hawaii.

I don’t know if it is thanks to Ebisu-sama, my son whose arrival in my life signaled the beginning of things finally going my way, or plain dumb luck, but last year ended up being the very best year ever in so many ways.

When you’ve already won the jackpot, it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to continue dropping quarters into the slot machine, and yet that is essentially what we did by returning to the Ebisu festival this year and trying our hand at the drawing again.

“Don’t get your hopes up,” my wife said.

“I know, I know,” I replied. “But still, it would be nice to get one of those boats with the seven lucky gods in it. I’ve always wanted one for the collection.”

Sure enough, Ebisu wasn’t as generous to us this year: we got a simple little wooden abacus. I suppose the message the gods are trying to tell us is that we should be more careful about how we spend money. Duly noted, Ebisu-sama!

[1] Ask your Japanese friends to try reading 一斗二升五合and most of them will be stumped. It is a riddle of sorts employing 斗, 升, 合 all of which are traditional Japanese measures of volume.

一斗 (itto, about 18 liters) is equal to ten 升 (shô, about 1.8 liters). 一斗, then, can be said to equal 五升の倍 (go shô no bai), which means “five shô doubled”. 五升の倍 (go shô no bai) is synonymous with 御商売 (go shôbai) which means “one’s business or trade”. Got that?

二升 (nishô). 升 can also be read masu. 二升 here is read “masu masu” which sounds like 益々 (masu masu), meaning “more and more”, “steadily”, and so on.

五合 (go gô, 5 x 0.18 liters, or 0.9 liters) is one half of a shô or 半升 (hanjô) which sounds the same as 繁盛 (hanjô, prosperity). So, putting it all together 一斗二升五合 can be read “Go-shôbai masu masu hanjô!” (御商売益々繁盛), meaning something to the effect that your business or trade will enjoy increasing prosperity.

Beware of Uncle Pervie

Every few days we get an email from the local elementary school reporting a "fushin-na jinbutsu" (不審な人物, suspicious person).

My first thought when reading these mails is usually "Geez, I hope someone isn't reporting me." Because of my running routine--I run like a burglar through about four different school districts dressed in BRIGHT pylon orange almost every morning--and the fact that I am a "guyjin", I stand out. There are often reports of my being seen running here or there.

The second thought is often "Geez, these perverts have not improved upon their game one iota in the four decades since I was a kid.”

Just the other day, a "young man" walked up to an elementary school girl and said, "Your father's been in an accident. Come with me and I'll take you to the hospital."

Oldest trick in the Perv Book!

The girl had the good sense to ask the man what her father's name was. When he couldn't answer, she ran away.

Today, a boy was approached by someone who promised to give him "something nice" if he came with him.

Second oldest trick!

Fortunately, this young boy also had the good sense to high-tail it.

Pitter Patter

Feels like Groundhog’s Day today.

3:30am

Liam wakes up, crying. We give him a half bottle, not too much because he’ll probably throw it all up. Ten minutes later, he’s asleep again. Figuring I might as well get up and get some work done, I go into the kitchen and make myself a cup of coffee.

4:00am

I’m at my desk. As I’m writing down my goals for December, one of which is to finish the current version of Rokuban once and for all, I hear the pitter-patter of Liam’s feet.

“What is it?”

“Mama. Mama.”

“Where’s Mama?”

“Mama ne-ne.”

“Mama’s sleeping?”

“Un.” (Yes.)

“Do you want to lie down with Daddy?”

“Un.”

I pick Liam up and take him back to the futon. He insists on lying just to my right. That’s where Eoghan usually sleeps, and in Liam’s mind it is a position of privilege. I scoot over so that my wife is on my left, Liam on my right, and Eoghan beyond him.

Before long, Eoghan wakes up, finds his position being usurped by the upstart Liam and begins kicking and pushing. I put Liam back between me and Rieko. After a while, both boys calm down and fall back asleep.

Or so I think. As soon as I sit up, Liam opens his eyes and gives me a look as if to say, “Where the fuck you going?”

I lie back down and rub his back, run my fingers through his long, curly hair. Every now and again, he looks to see if I am still there. When he’s finally snoring, I head back to my office.

4:30am

My coffee is getting cold. I’m getting cold. The wind is still strong outside. The windows whistle with excitement. I hear the bedroom door slide open, then closed, the hallway door open, steps, then Liam’s voice, “Daddy. Daddy.”

I open the door and find Liam standing there, rubbing his eyes, his hair wild.

“Hold me.”

I pick him up and take him back to the futon. He’s asleep in no time.

5:00am

My coffee is now cold. I’ve been up for an hour and a half and all I have written is: “Finish Rokuban.”

Pitter-patter

Sighing, “At this rate, I won’t be finishing anything.”

I pick Liam up and feel his diaper. Full tank. I get a fresh diaper and carry him back to the bedroom.

The nice thing about Liam is that for a two-year-old he is remarkably meticulous. He closes doors behind himself, he puts the caps back on the pens when he’s finished drawing, he returns his plates to the kitchen after eating, he throws his diapers in the garbage, he goes to the toilet by himself, and when he’s done he removes the potty trainer and puts it back in its place. Eoghan, on the other hand, has a habit of tossing everything onto the ground.

So, I change the boy’s diaper and lie down next to him one more time.

“Liam, baby.”

That means Liam wants to lie down on Daddy’s chest. He crawls up on top of me, yawns, and falls asleep.

The boy is getting big. In the past few months, he grew about four or five centimeters. As he is lying on my chest, his toes touch my knees and the top of his head is only a few months of growth away from touching my chin. I give that mop of hair of his a kiss, then slowly lower him down to my side.

5:30am

I make myself a fresh cup of coffee and head back down the hall to my office.

We have finally managed to get through the night without either of the boys vomiting. Progress! Now to make some progress on my writing.

Irreconcilable

Went out with an old(ish) friend for the first time in years tonight.

Before she got knocked up, we used to meet up about once a week, sometimes more. After the pregnancy, she like many women in Japan focused on raising her child. At about the same time a number of good drinking buddies of mine (all women) were transferred out of Fukuoka. It was as if all my close friends had been ripped away from me.

But then, I married and before long became a father myself.

In the meantime, the friend separated from her husband, got pregnant again, postponed the divorce and . . . six years passed like one whirl on a merry-go-round.

We had a couple of drinks at one place, then went to another place and had a few more. It was like old times, but we weren't young, single, or childless anymore.

I have written about this woman before in my book "Kampai"--buy it Goddammit--but tonight I realized there were a lot of things I still didn't know about her.

I knew she was from a broken home, but didn't know the details until tonight.

Her parents divorced when she was still in elementary school. Her mother worked as a hostess at a snack to support her and her younger brother. She bandied around schools due to her mother's frequent moving. Never in the better parts of town, of course.

Still, she managed to grow up into a descent, if somewhat brusque adult. (I think it was the coarseness of her character that attracted me to her in the first place.)

Tonight she told me that she had no contact with her father for over two decades when one day she was at a DIY center where she saw a man who looked just like her. She asked him if he was a Mr. So-and-so and he said yes.

"I'm your daughter."

Imagine that.

Now consider that that particular day was her father's very last day of work. He was retiring.

She said the two of them shed a lot of tears and I can imagine it. I almost started crying myself when I heard the story.

The man had since married and had more children, so their chance meeting was awkward to say the least. Since that day, the two have remained in contact, but always in secret. She says she feels like a lover more than a daughter the way they have to sneak around just to meet. But, I guess, it's better than pretending to be strangers.

Sometimes Japanese over-complicate relationships, especially the ones which have turned sour.

Enough.

http://www.aonghascrowe.com/journal/2013/2/1/divorce-japanese-style.html